The hoi polloi are running fast towards the banner marked “Internet of Things“. They are running at full speed chanting “I-o-T, I-o-T, I-o-T” all along the way. But for the most part, they are each running towards something different. For some, it is a network of sensors; for others, it is a network of processors; for still others, it is a previously unconnected and unnetworked embedded system but now connected and attached to a network; some say it is any of those things connected to the cloud; and there are those who say it is simply renaming whatever they already have and including the descriptive marketing label “IoT” or “Internet of Things” on the box.

The hoi polloi are running fast towards the banner marked “Internet of Things“. They are running at full speed chanting “I-o-T, I-o-T, I-o-T” all along the way. But for the most part, they are each running towards something different. For some, it is a network of sensors; for others, it is a network of processors; for still others, it is a previously unconnected and unnetworked embedded system but now connected and attached to a network; some say it is any of those things connected to the cloud; and there are those who say it is simply renaming whatever they already have and including the descriptive marketing label “IoT” or “Internet of Things” on the box.

So what is it? Why the excitement? And what can it do?

At its simplest, the Internet of Things is a collections of endpoints of some sort each of which has a sensor or a number of sensors, a processor, some memory and some sort of wireless connectivity. The endpoints are then connected to a server – where “server” is defined in the broadest possible sense. It could be a phone, a tablet, a laptop or desktop, a remote server farm or some combination of all of those (say, a phone that then talks to a server farm). Along the transmission path, data collected from the sensors goes through increasingly higher levels of analysis and processing. For instance, at the endpoint itself raw data may be displayed or averaged or corrected and then delivered to the server and then stored in the cloud. Once in the cloud, data can be analyzed historically, compared with other similarly collected data, correlated to other related data or even unrelated data in an attempt to search for unexpected or heretofore unseen correlations. Fully processed data can then be delivered back to the user in some meaningful way. Perhaps the processed data could be displayed as trend display or as a prescriptive suite of actions or recommendations. And, of course, the fully analyzed data and its correlations could also be sold or otherwise used to target advertising or product or service recommendations.

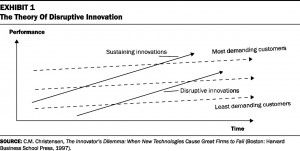

There is a further enhancement to this collection of endpoints and associated data analysis processes described in my basic IoT system. The ‘things’ on this Internet of Things could also use to the data it collects to improve itself. This could include identifying missing data elements or sensor readings, bad timing assumptions or other ways to improve the capabilities of the overall system. If the endpoints are reconfigurable either through programmable logic (like Field Programmable Gate Arrays) or through software updates then new hardware or software images could be distributed with enhancements (or, dare I say, bug fixes) throughout the system to provide it with new functionality. This makes the IoT system both evolutionary and field upgradeable. It extends the deployment lifetime of the device and could potentially extend the time in market at both the beginning and the end of the product life cycle. You could get to market earlier with limited functionality, introduce new features and enhancement post deployment and continue to add innovations when the product might ordinarily have been obsoleted.

Having defined an ideal IoT system, the question becomes how does one turn it into a business? The value of these IoT applications are based on the collection of data over time and the processing and interpretation (mining) of said data. As more data are collected over time the value of the analysis increases (but likely asymptotically approaching some maximal value). The data analysis could include information like:

- Your triathlon training plan is on track, you ought to taper the swim a bit and increase the running volume to 18 miles per week.

- The drive shaft on your car will fail in the next 1 to 6 weeks – how about I order one for you and set up an appointment at the dealership?

- If you keep eating the kind of food you have for the past 4 days, you will gain 15 pounds by Friday.

The above sample analysis is obviously from a variety of different products or systems but the idea is that by mining collected and historical data from you, and maybe even people ‘like’ you, certain conclusions may be drawn.

Since the analysis is continuous and the feedback unsynchronized to any specific event or time, the fees for these services would have to be subscription-based. A small charge every month would deliver the analysis and prescriptive suggestions as and when needed.

This would suggest that when you a buy a car instead of an extended service contract that you pay for as a lump sum upfront, you pay, say, $5 per month and the IoT system is enabled on your car and your car will schedule service with a complete list of required parts and tasks exactly when and as needed.

Similarly in the health services sector, your IoT system collects all of your biometric data automatically, loads your activity data to Strava, alerts you to suspicious bodily and vital sign changes and perhaps even calls the doctor to set up your appointment.

The subscription fees should be low because they provide for efficiencies in the system that benefit both the subscriber and the service provider. The car dealer orders the parts they need when they need them, reducing inventory, providing faster turnaround of cars, obviating the need for overnight storage of cars and payment for rentals.

Doctors see patients less often and then only when something is truly out of whack.

And on and on.

Certainly the possibility for tiered levels of subscription may make sense for some businesses. There may be ‘free’ variants that provide limited but still useful information to the subscriber but at the cost of sharing their data for broader community analysis. Paid subscribers who share their data for use in broader community analysis may get reduced subscription rates. There are obvious many possible subscription models to investigate.

These described industry capabilities and direction facilitated by the Internet of Things are either pollyannaish or visionary. It’s up to us to find out. But for now, what do you think?