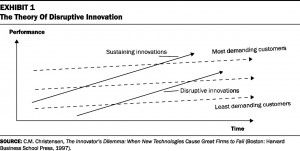

Everyone who is anyone loves bandying about the name of Clayton Christensen, the famed Professor of Business Administration at the Harvard Business School, who is regarded as one of the world’s top experts on innovation and growth and who is most famous for coining the term “disruptive innovation“. Briefly, the classical meaning of the term is as follows. A company, usually a large one, focuses on serving the high end, high margin part of their business and in doing so they provide an opening at the low end, low margin market segment. This allows for small nimble, hungry innovators to get a foothold in the market by providing cheap but good enough products to the low end who are otherwise forsaken by the large company who is only willing to provide high priced, over-featured products. These small innovators use their foothold to innovate further upmarket providing products of increasingly better functionality at lower cost that the Big Boys at the high end. The Big Boys are happy with this because those lower margin products are a lot of effort for little payback and “The Market” rewards them handsomely for doing incremental innovation at the high end and maintaining high margins. In the fullness of time, the little scrappy innovators disrupt the market with cheaper, better and more innovative solutions and products that catch up to and eclipse the offerings of the Big Boys, catching them off guard and the once large corporations, with their fat margins, become small meaningless boutique firms. Thus the market is disrupted and the once regal and large companies, even though they followed all the appropriate rules dictated by “The Market”, falter and die.

Everyone who is anyone loves bandying about the name of Clayton Christensen, the famed Professor of Business Administration at the Harvard Business School, who is regarded as one of the world’s top experts on innovation and growth and who is most famous for coining the term “disruptive innovation“. Briefly, the classical meaning of the term is as follows. A company, usually a large one, focuses on serving the high end, high margin part of their business and in doing so they provide an opening at the low end, low margin market segment. This allows for small nimble, hungry innovators to get a foothold in the market by providing cheap but good enough products to the low end who are otherwise forsaken by the large company who is only willing to provide high priced, over-featured products. These small innovators use their foothold to innovate further upmarket providing products of increasingly better functionality at lower cost that the Big Boys at the high end. The Big Boys are happy with this because those lower margin products are a lot of effort for little payback and “The Market” rewards them handsomely for doing incremental innovation at the high end and maintaining high margins. In the fullness of time, the little scrappy innovators disrupt the market with cheaper, better and more innovative solutions and products that catch up to and eclipse the offerings of the Big Boys, catching them off guard and the once large corporations, with their fat margins, become small meaningless boutique firms. Thus the market is disrupted and the once regal and large companies, even though they followed all the appropriate rules dictated by “The Market”, falter and die.

Examples of this sort of evolution are many. The Japanese automobile manufacturers used this sort of approach to disrupt the large American manufacturers in the 70s and 80s; the same with Minicomputers versus Mainframes and then PCs versus Minicomputers; to name but a few. But when you think about it, sometimes disruption comes “from above”. Consider the iPod. Remember when Apple introduced their first music player? They weren’t the first-to-market as there were literally tens of MP3 players available. They certainly weren’t the cheapest as about 80% of the portable players had a price point well-below Apple’s $499 MSRP. The iPod did have more features than most other players available and was in many ways more sophisticated – but $499? This iPod was more expensive, more featured, higher priced, had more space on it for storage than anyone could ever imagine needing and had bigger margins than any other similar device on the market. And it was a huge hit. (I personally think that the disruptive part was iTunes that made downloading music safe, legal and cheap at a time when the RIAA was making headlines by suing ordinary folks for thousands of dollars for illegal music downloads – but enough about me.) From the iPod, Apple went on to innovate a few iPod variants, the iPhone and the iPad as well as incorporating some of the acquired knowledge into the Mac.

And now, I think, another similarly modeled innovation is upon us. Consider Tesla Motors. Starting with the now-discontinued Roadster – a super high end luxury 2 seater sport vehicle that was wholly impractical and basically a plaything for the 1%. But it was a great platform to collect data and learn about batteries, charging, performance, efficiency, design, use and utility. Then the Model S that, while still quite expensive, brought that price within reach of perhaps the 2% or even the 3%. In Northern California, for instance, Tesla S cars populate the roadways seemingly with the regularity of VW Beetles. Of course, part of what makes them seem so common is that their generic luxury car styling makes them nearly indistinguishable, at first glace, from a Lexus, Jaguar, Infiniti, Maserati, Mercedes Benz, BMW and the like. The choice of styling is perhaps yet another avenue of innovation. Unlike, the Toyota Prius whose iconic design became a “vector” sending a message to even the casual observer about the driver and perhaps the driver’s social and environmental concerns. The message of the Tesla’s generic luxury car design to the casual observer merely seems to be “I’m rich – but if you want to learn more about me – you better take a closer look”. Yet even attracting this small market segment, Tesla was able to announce profitability for the first time.

With their third generation vehicle, Tesla promises to reduce their selling price by 40% over the current Model S . This would bring the base price to about $30,000 which is within the average selling price of new cars in the United States. Even without the lower priced vehicle available, Tesla is being richly rewarded by The Market thanks to a good product (some might say great), some profitability, excellent and savvy PR and lots and lots of promise of a bright future.

But it is the iPod model all over again. Tesla is serving the high end and selling top-of-the-line technology. They are developing their technology within a framework that is bound mostly by innovation and their ability to innovate and not by cost or selling price. They are also acting in a segment of the market that is not really well-contested (high-end luxury electric cars). This gives them freedom from the pressures of competition and schedules – which gives them an opportunity to get things right rather than rushing out ‘something’ to appease the market. And with their success in that market, they are turning around and using what they have learned to figure out how to build the same thing (or a similar thing) cheaper and more efficiently to bring the experience to the masses (think: iPod to Nano to Shuffle). They will also be able thusly to ease their way into competing at the lower end with the Nissan Leaf, Chevy Volt, the Fiat 500e and the like.

Maybe the pathway to innovation really is from the high-end down to mass production?

1 Comment to 'The iPod Car'

November 17, 2013

Very interesting article.

As you know I am a car guy. I have totally restored many cars.

Thank you for including me.

Jim

Leave a comment